Unicode, UTF8 & Character Sets: The Ultimate Guide

This is a story that dates back to the earliest days of computers. The story has a plot, well, sort of. It has competition and intrigue, as well as traversing oodles of countries and languages. There is conflict and resolution, and a happyish ending. But the main focus are the characters: 110,116 of them. By the end of the story, they will all find their own unique place in this world.

This article will follow a few of those characters more closely, as they journey from Web server to browser, and back again. Along the way, you’ll find out more about the history of characters, character sets, Unicode and UTF-8, and why question marks and odd accented characters sometimes show up in databases and text files.

Warning: This article contains lots of numbers, including a bit of binary — best approached after your morning cup of coffee.

ASCII

Computers only deal in numbers and not letters, so it’s important that all computers agree on which numbers represent which letters.

Let’s say my computer used the number 1 for A, 2 for B, 3 for C, etc and yours used 0 for A, 1 for B, etc. If I sent you the message HELLO, then the numbers 8, 5, 12, 12, 15 would whiz across the wires. But for you 8 means I, so you would receive and decode it as IFMMP. To communicate effectively, we would need to agree on a standard way of encoding the characters.

To this end, in the 1960s the American Standards Association created a 7-bit encoding called the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII). In this encoding HELLO is 72, 69, 76, 76, 79 and would be transmitted digitally as 1001000 1000101 1001100 1001100 1001111. Using 7 bits gives 128 possible values from 0000000 to 1111111, so ASCII has enough room for all lower case and upper case Latin letters, along with each numerical digit, common punctuation marks, spaces, tabs and other control characters. In 1968, US President Lyndon Johnson made it official — all computers must use and understand ASCII.

Trying It Yourself

There are plenty of ASCII tables available, displaying or describing the 128 characters. Or you can make one of your own with a little bit of CSS, HTML and Javascript, most of which is to get it to display nicely:

<html>

<body>

<style type="text/css">p {float: left; padding: 0 15px; margin: 0; font-size: 80%;}</style>

<script type="text/javascript">

for (var i=0; i<128; i++) document.writeln ((i%32?’:'<p>') + i + ': ' + String.fromCharCode (i) + '<br>');

</script>

</body>

</html>This will display a table like this:

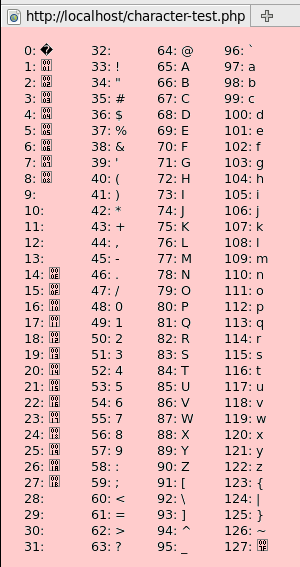

Do-It-Yourself Javascript ASCII table viewed in Firefox

The most important bit of this is the Javascript String.fromCharCode function. It takes a number and turns it into a character. In fact, the following four lines of HTML and Javascript all produce the same result. They all get the browser to display character numbers 72, 69, 76, 76 and 79:

HELLO

HELLO

<script>document.write ("HELLO");</script>

<script>document.write (String.fromCharCode (72,69,76,76,79));</script>Also notice how Firefox displays the unprintable characters (like backspace and escape) in the first column. Some browsers show blanks or question marks. Firefox squeezes four hexadecimal digits into a small box.

The Eighth Bit

Teleprinters and stock tickers were quite happy sending 7 bits of information to each other. But the new fangled microprocessors of the 1970s preferred to work with powers of 2. They could process 8 bits at a time and so used 8 bits (aka a byte or octet) to store each character, giving 256 possible values.

An 8 bit character can store a number up to 255, but ASCII only assigns up to 127. The other values from 128 to 255 are spare. Initially, IBM PCs used the spare slots to represent accented letters, various symbols and shapes and a handful of Greek letters. For instance, number 200 was the lower left corner of a box: ╚, and 224 was the Greek letter alpha in lower case: α. This way of encoding the letters was later given the name code page 437.

However, unlike ASCII, characters 128-255 were never standardized, and various countries started using the spare slots for their own alphabets. Not everybody agreed that 224 should display α, not even the Greeks. This led to the creation of a handful of new code pages. For example, in Russian IBM computers using code page 885, 224 represents the Cyrillic letterЯ. And in Greek code page 737, it is lower case omega: ω.

Even then there was disagreement. From the 1980s Microsoft Windows introduced its own code pages. In the Cyrillic code page Windows-1251, 224 represents the Cyrillic letter a, andЯ is at 223.

In the late 1990s, an attempt at standardization was made. Fifteen different 8 bit character sets were created to cover many different alphabets such as Cyrillic, Arabic, Hebrew, Turkish, and Thai. They are called ISO-8859-1 up to ISO-8859-16 (number 12 was abandoned). In the Cyrillic ISO-8859-5, 224 represents the letter р, and Я is at 207.

So if a Russian friend sends you a document, you really need to know what code page it uses. The document by itself is just a sequence of numbers. Character 224 could be Я, a or р. Viewed using the wrong code page, it will look like a bunch of scrambled letters and symbols.

(The situation isn’t quite as bad when viewing Web pages — as Web browsers can usually detect a page’s character set based on frequency analysis and other such techniques. But this is a false sense of security — they can and do get it wrong.)

Trying It Yourself

Code pages are also known as character sets. You can explore these character sets yourself, but you have to use PHP or a similar server side language this time (roughly because the character needs to be in the page before it gets to the browser). Save these lines in a PHP file and upload it to your server:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="ISO-8859-5">

</head>

<body>

<style type="text/css">p {float: left; padding: 0 15px; margin: 0; font-size: 80%;}</style>

<?php for ($i=0; $i<256; $i++) echo ($i%32?’:'<p>') . $i . ': ' . chr ($i) . '<br>'; ?>

</body>

</html>This will display a table like this:

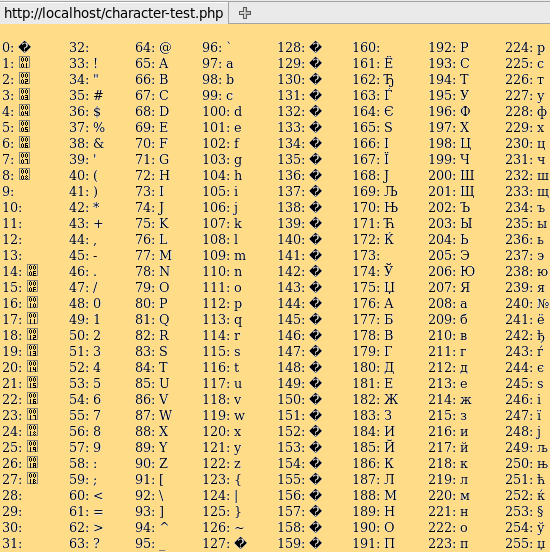

Cyrillic character set ISO-8859-5 viewed in Firefox

The PHP function chr does a similar thing to Javascript’s String.fromCharCode. For example chr(224) embeds the number 224 into the Web page before sending it to the browser. As we’ve seen above, 224 can mean many different things. So, the browser needs to know which character set to use to display the 224. That’s what the first line above is for. It tells the browser to use the Cyrillic character set ISO-8858-5:

<meta charset="ISO-8859-5">If you exclude thecharset line, then it will display using the browser’s default. In countries with Latin-based alphabets (like the UK and US), this is probably ISO-8859-1, in which case 224 is an a with grave accent: à. Try changing this line to ISO-8859-7 or Windows-1251 and refresh the page. You can also override the character set in the browser. In Firefox go to View > Character Encoding. Swap between a few to see what effect it has. If you try to display more than 256 characters, the sequence will repeat.

Summary Circa 1990

This is the situation in about 1990. Documents can be written, saved and exchanged in many languages, but you need to know which character set they use. There is also no easy way to use two or more non-English alphabets in the same document, and alphabets with more than 256 characters like Chinese and Japanese have to use entirely different systems.

Finally, the Internet is coming! Internationalization and globalization is about to make this a much bigger issue. A new standard is required.

Unicode To The Rescue

Starting in the late 1980s, a new standard was proposed – one that would assign a unique number (officially known as a code point) to every letter in every language, one that would have way more than 256 slots. It was called Unicode. It is now in version 6.1 and consists of over 110,000 code points. If you have a few hours to spare you can watch them all whiz past.

The first 128 Unicode code points are the same as ASCII. The range 128-255 contains currency symbols and other common signs and accented characters (aka characters with diacritical marks), and much of it is borrowed ISO-8859-1. After 256 there are many more accented characters. After 880 it gets into Greek letters, then Cyrillic, Hebrew, Arabic, Indic scripts, and Thai. Chinese, Japanese and Korean start from 11904 with many others in between.

This is great – no more ambiguity – each letter is represented by its own unique number. Cyrillic Я is always 1071 and Greek α is always 945. 224 is always à, and H is still 72. Note that these Unicode code points are officially written in hexadecimal preceded by U+. So the Unicode code point H is usually written as U+0048 rather than 72 (to convert from hexadecimal to decimal: 4*16+8=72).

The major problem is that there are more than 256 of them. The characters will no longer fit into 8 bits. However Unicode is not a character set or code page. So officially that is not the Unicode Consortium’s problem. They just came up with the idea and left someone else to sort out the implementation. That will be discussed in the next two sections.

Unicode Inside The Browser

Unicode does not fit into 8 bits, not even into 16. Although only 110,116 code points are in use, it has the capability to define up to 1,114,112 of them, which would require 21 bits.

However, computers have advanced since the 1970s. An 8 bit microprocessor is a bit out of date. New computers now have 64 bit processors, so why can’t we move beyond an 8 bit character and into a 32 bit or 64 bit character?

The first answer is: we can!

A lot of software is written in C or C++, which supports a “wide character”. This is a 32 bit character called wchar_t. It is an extension of C’s 8 bit char type. Internally, modern Web browsers use these wide characters (or something similar) and can theoretically quite happily deal with over 4 billion distinct characters. This is plenty for Unicode. So — internally, modern Web browers use Unicode.

Trying It Yourself

The Javascript code below is similar to the ASCII code above, except it goes up to a much higher number. For each number, it tells the browser to display the corresponding Unicode code point:

<html>

<body>

<style type="text/css">p {float: left; padding: 0 15px; margin: 0; font-size: 80%;}</style>

<script type="text/javascript">

for (var i=0; i<2096; i++)

document.writeln ((i%256?’:'<p>') + i + ': ' + String.fromCharCode (i) + '<br>');

</script>

</body>

</html>It will output a table like this:

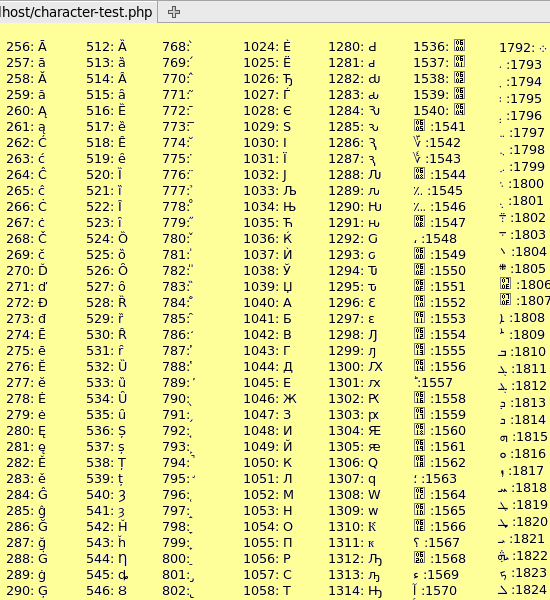

A selection of Unicode code points viewed in Firefox

The screenshot above only shows a subset of the first few thousand code points output by the Javascript. The selection includes some Cyrillic and Arabic characters, displayed right-to-left.

The important point here is that Javascript runs completely in the Web browser where 32 bit characters are perfectly acceptable. The Javascript function String.fromCharCode(1071) outputs the Unicode code point 1071 which is the letter Я.

Similarly if you put the HTML entity Я into an HTML page, a modern Web browser would display Я. Numerical HTML entities also refer to Unicode.

On the other hand, the PHP function chr(1071) would output a forward slash / because the chr function only deals with 8 bit numbers up to 256 and repeats itself after that, and 1071%256=47 which has been a / since the 1960s.

UTF-8 To The Rescue

So if browsers can deal with Unicode in 32 bit characters, where is the problem? The problem is in the sending and receiving, and reading and writing of characters.

The problem remains because:

- A lot of existing software and protocols send/receive and read/write 8 bit characters

- Using 32 bits to send/store English text would quadruple the amount of bandwidth/space required

Although browsers can deal with Unicode internally, you still have to get the data from the Web server to the Web browser and back again, and you need to save it in a file or database somewhere. So you still need a way to make 110,000 Unicode code points fit into just 8 bits.

There have been several attempts to solve this problem such as UCS2 and UTF-16. But the winner in recent years is UTF-8, which stands for Universal Character Set Transformation Format 8 bit.

UTF-8 is a clever. It works a bit like the Shift key on your keyboard. Normally when you press the H on your keyboard a lower case “h” appears on the screen. But if you press Shift first, a capital H will appear.

UTF-8 treats numbers 0-127 as ASCII, 192-247 as Shift keys, and 128-192 as the key to be shifted. For instance, characters 208 and 209 shift you into the Cyrillic range. 208 followed by 175 is character 1071, the Cyrillic Я. The exact calculation is (208%32)*64 + (175%64) = 1071. Characters 224-239 are like a double shift. 226 followed by 190 and then 128 is character 12160: ⾀. 240 and over is a triple shift.

UTF-8 is therefore a multi-byte variable-width encoding. Multi-byte because a single character like Я takes more than one byte to specify it. Variable-width because some characters like H take only 1 byte and some up to 4.

Best of all it is backward compatible with ASCII. Unlike some of the other proposed solutions, any document written only in ASCII, using only characters 0-127, is perfectly valid UTF-8 as well — which saves bandwidth and hassle.

Trying It Yourself

This is a different experiment. PHP embeds the 6 numbers mentioned above into an HTML page: 72, 208, 175, 226, 190, 128. The browser interprets those numbers as UTF-8, and internally converts them into Unicode code points. Then Javascript outputs the Unicode values. Try changing the character set from UTF-8 to ISO-8859-1 and see what happens:

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

</head>

<body>

<p>Characters embedded in the page:<br>

<span id="chars"><?php echo chr(72).chr(208).chr(175).chr(226).chr(190).chr(128); ?></span>

<p>Character values according to Javascript:<br>

<script type="text/javascript">

function ShowCharacters (s) {var r=’; for (var i=0; i<s.length; i++)

r += s.charCodeAt (i) + ': ' + s.substr (i, 1) + '<br>'; return r;}

document.writeln (ShowCharacters (document.getElementById('chars').innerHTML));

</script>

</body>

</html>If you are in a hurry, this is what it will look like:

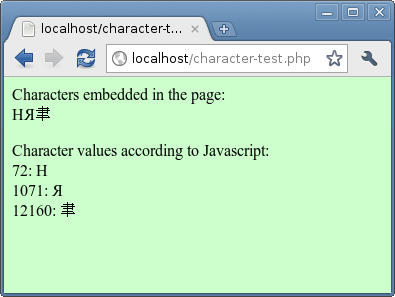

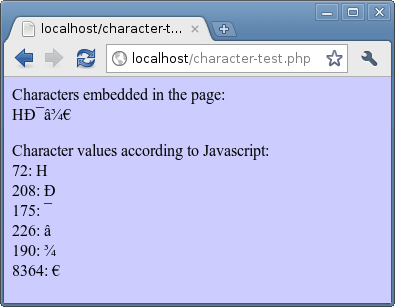

The sequence of numbers above shown using the UTF-8 character set

Same sequence of numbers shown using the ISO-8859-1 character set

If you display the page using the UTF-8 character set, you will see only 3 characters: HЯ⾀. If you display it using the character set ISO-8859-1, you will see six separate characters:HЯ⾀ . This is what is happening:

- On your Web server, PHP is embedding the numbers 72, 208, 175, 226, 190 and 128 into a Web page

- The Web page whizzes across the Internet from the Web server to your Web browser

- The browser receives those numbers and interprets them according to the character set

- The browser internally represents the characters using their Unicode values

- Javascript outputs the corresponding Unicode values

Notice that when viewed as ISO-8859-1 the first 5 numbers are the same (72, 208, 175, 226, 190) as their Unicode code points. This is because Unicode borrowed heavily from ISO-8859-1 in that range. The last number however, the euro symbol €, is different. It is at position 128 in ISO-8859-1 and has the Unicode value 8364.

Summary Circa 2003

UTF-8 is becoming the most popular international character set on the Internet, superseding the older single-byte character sets like ISO-8859-5. When you view or send a non-English document, you still need to know what character set it uses. For widest interoperability, website administrators need to make sure all their web pages use the UTF-8 character sets.

Perhaps the Ð looks familiar — it will sometimes show up if you try to view Russian UTF-8 documents. The next section describes how character sets get confused and end up storing things wrongly in a database.

Lots Of Problems

As long as everybody is speaking UTF-8, this should all work swimmingly. If they aren’t, then characters can get mangled. To explain way, imagine a typical interaction a website, such as a user making a comment on a blog post:

- A Web page displays a comment form

- The user types a comment and submits.

- The comment is sent back to the server and saved in a database.

- The comment is later retrieved from the database and displayed on a Web page

This simple process can go wrong in lots of ways and produce the following types of problems:

HTML Entities

Pretend for a moment that you don’t know anything about character sets — erase the last 30 minutes from your memory. The form on your blog will probably display itself using the character set ISO-8859-1. This character set doesn’t know any Russian or Thai or Chinese, and only a little bit of Greek. If you attempt to copy and paste any into the form and press Submit, a modern browser will try to convert it into HTML numerical entities like Я for Я.

That’s what will get saved in your database, and that’s what will be output when the comment is displayed — which means it will display fine on a Web page, but cause problems when you try to output it to a PDF or email, or run text searches for it in a database.

Confused Characters

How about if you operate a Russian website, and you have not specified a character set in your Web page? Imagine a Russian user whose default character set is ISO-8859-5. To say “hi”, they might type Привет. When the user presses Submit, the characters are encoded according to the character set of the sending page. In this case, Привет is encoded as the numbers 191, 224, 216, 210, 213 and 226. Those numbers will get sent across the Internet to the server, and saved like that into a database.

If somebody later views that comment using ISO-8859-5, they will see the correct text. But if they view using a different Russian character set like Windows-1251, they will see їаШТХв. It’s still Russian, but makes no sense.

Accented Characters with Lots of Vowels

If someone views the same comment using ISO-8859-1, they will see ¿àØÒÕâ instead of Привет. A longer phrase like Я тоже рада Вас видеть (“nice to see you” in a formal way to a female), submitted as ISO-8859-5, will show up in ISO-8859-1 as Ï âÞÖÕ àÐÔÐ. It looks like that because the 128-255 range of ISO-8859-1 contains lots of vowels with accents.

So if you see this sort of pattern, it’s probably because text has been entered in a single byte character set (one of the ISO-8859s or Windows ones) and is being displayed as ISO-8859-1. To fix the text, you’ll need to figure out which character set it was entered as, and resubmit it as UTF-8 instead.

Alternating Accented Characters

What if the user submitted the comment in UTF-8? In that case the Cyrillic characters which make up the word Привет would each get sent as 2 numbers each: 208⁄159, 209⁄128, 208⁄184, 208⁄178, 208⁄181 and 209⁄130. If you viewed that in ISO-8859-1 it would look like: Привет.

Notice that every other character is a Ð or Ñ. Those characters are numbers 208 and 209, and they tell UTF-8 to switch to the Cyrillic range. So if you see a lot of Ð and Ñ, you can assume that you are looking at Russian text entered in UTF-8, viewed as ISO-8859-1. Similarly, Greek will have lots of Î and Ï, 206 and 207. And Hebrew has alternating ×, number 215.

Vowels Before a Pound and Copyright Sign

A very common issue in the UK is the currency symbol £ getting converted into £. This is exactly the same issue as above with a coincidence thrown in to add confusion. The £ symbol has the Unicode and ISO-8859-1 value of 163. Recall that in UTF-8 any character over 127 is represented by a sequence of two or more numbers. In this case, the UTF-8 sequence is 194⁄163. Mathematically, this is because (194%32)*64 + (163%64) = 163.

Visually it means that the if you view the UTF-8 sequence using ISO-8859-1, it appears to gain a  which is character 194 in ISO-8859-1. The same thing happens for all Unicode code points 161-191, which includes © and ® and ¥.

So if your £ or © suddenly inherit a Â, it is because they were entered as UTF-8.

Black Diamond Question Marks

How about the other way around? If you enter Привет as ISO-8859-5, it will get saved as the numbers shown above: 191, 224, etc. If you then try to view this as UTF-8, you may well see lots of question marks inside black diamonds: �. The browser displays these when it can’t make sense of the numbers it is reading.

UTF-8 is self-synchronzising. Unlike other multi-byte character encodings, you always know where you are with UTF-8. If you see a number 192-247, you know you are at the beginning of a multi-byte sequence. If you see 128-191 you know you are in the middle of one. There’s no danger of missing the first number and garbling the rest of the text.

This means that in UTF-8, the sequence 191 followed by 224 will never occur naturally, so the browser doesn’t know what to do with it and displays �� instead.

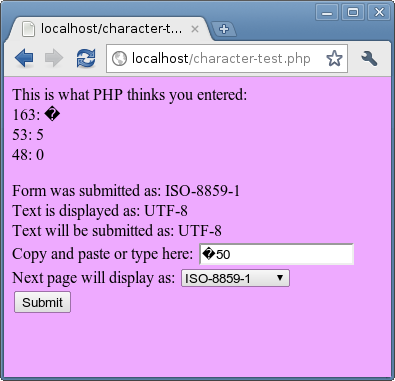

This can also cause £ and © related problems. £50 in ISO-8859-1 is the numbers 163, 53 and 48. The 53 and 48 cause no issues, but in UTF-8, 163 can never occur by itself, so this will show up as �50. Similarly if you see �2012, it is probably because ©2012 was input as ISO-8859-1 but is being displayed as UTF-8.

Blanks, Question Marks and Boxes

Even if they are fully up-to-speed with UTF-8 and Unicode, a browser still may not know how to display a character. The first few ASCII characters 1-31 are mostly control sequences for teleprinters (things like Acknowledge and Stop). If you try to display them, a browser might show a ? or a blank or a box with tiny numbers inside it.

Also, Unicode defines over 110,000 characters. Your browser may not have the correct font to display all of them. Some of the more obscure characters may also get shown as ? or blank or a small box. In older browsers, even fairly common non-English characters may show as boxes.

Older browsers may also behave differently for some of the issues above, showing ? and blank boxes more often.

Databases

The discussion above has avoided the middle step in the process — saving data to a database. Databases like MySQL can also specify a character set for a database, table or column. But it is less important that the Web pages’ character set.

When saving and retrieving data, MySQL deals just with numbers. If you tell it to save number 163, it will. If you give it 208⁄159 it will save those two numbers. And when you retrieve the data, you’ll get the same two numbers back.

The character set becomes more important when you use database functions to compare, convert and measure the data. For example, theLENGTH of a field may depend on its character set, as do string comparisons usingLIKE and =

Character sets and collations in MySQL are an in-depth subject. It’s not simply a case of changing the character set of a table to UTF-8. There are further SQL commands to take into account to make sure the data goes in and out in the right format as well.

Trying It Yourself

The following PHP and Javascript code allows you to experiment with all these issues. You can specify which character set is used to input and output text, and you can see what the browser thinks about it too.

<?php

$charset = $_POST['charset']; if (!$charset) $charset = 'ISO-8859-1';

$string = $_POST['string'];

if ($string) {

echo '<p>This is what PHP thinks you entered:<br>';

for ($i=0; $i<strlen($string); $i++) {$c=substr ($string,$i,1); echo ord ($c).': '.$c.' <br/>';}

}

?>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="<?=$charset?>">

</head>

<body>

<form method="post">

<input name="lastcharset" type="hidden" value="<?php echo $charset?>"/>

Form was submitted as: <?php echo $_POST['lastcharset']?><br/>

Text is displayed as: <?php echo $charset?><br/>

Text will be submitted as: <?php echo $charset?><br/>

Copy and paste or type here:

<input name="string" type="text" size="20" value="<?php echo $string?>"/><br/>

Next page will display as:

<select name="charset"><option>ISO-8859-1<option>ISO-8859-5

<option>Windows-1251<option>ISO-8859-7<option>UTF-8</select><br/>

<input type="submit" value="Submit" onclick="ShowCharacters (this.form.string.value); return 1;"/>

</form>

<script type="text/javascript">

function ShowCharacters (s) {

var r='You entered:';

for (var i=0; i<s.length; i++) r += 'n' + s.charCodeAt (i) + ': ' + s.substr (i, 1);

alert (r);

}

</script>

</body>

</html>This is an example of the code in action. The numbers at the top are the numerical values of each of the characters and their representation (when viewed individually) in the current character set:

Example of inputting and output in different character sets. This shows a £ sign turning into a � in Google Chrome.

The page above shows the previous, current and future character sets. You can use this code to quickly see how text can get really mangled. For example, if you pressed Submit again above, the � has Unicode code point 65533 which is 239/191/189 in UTF-8 and will be displayed as �50 in ISO-8859-1. So if you ever get £ symbols turning into �, that is probably the route they took.

Note that the select box at the bottom will change back to ISO-8859-1 each time.

One Solution

All the encoding problems above are caused by text being submitted in one character set and viewed in another. The solution is to make sure that every page on your website uses UTF-8. You can do this with one of these lines immediately after the <head> tag:

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=UTF-8">It has to be one of the first things in your Web page, as it will cause the browser to look again at the page in a whole new light. For speed and efficiency, it should do this as soon as possible.

You can also specify UTF-8 in your MySQL tables, though to fully use this feature, you’ll need to delve deeper.

Note that users can still override the character set in their browsers. This is rare, but does mean that this solution is not guaranteed to work. For extra safety, you could implement a back-end check to ensure data is arriving in the correct format.

Existing Websites

If your website has already been collecting text in a variety of languages, then you will also need to convert your existing data into UTF-8. If there is not much of it, you can use a PHP page like the one above to figure out the original character set, and use the browser to convert the data into UTF-8.

If you have lots of data in various character sets, you’ll need to first detect the character set and then convert it. In PHP you can use mb_detect_encoding to detect and iconv to convert. Reading the comments for mb_detect_encoding, it looks like quite a fussy function, so be sure to experiment to make sure you are using it properly and getting the right results.

A potentially misleading function is utf8_decode. It turns UTF-8 into ISO-8859-1. Any characters not available in ISO-8859-1 (like Cyrillic, Greek, Thai, etc) are turned into question marks. It’s misleading because you might have expected more from it, but it does the best it can.

Summary

This article has relied heavily on numbers and has tried to leave no stone unturned. Hopefully it has provided an exhaustive understanding of character sets, Unicode, UTF-8 and the various problems that can arise. The morals of the story are:

- You need to know the character set in order to make sense of non-Latin text,

- Internally, browsers use Unicode to represent characters,

- Make sure all your Web pages specify the UTF-8 character set.

For a slightly different approach to this subject, this 2003 character set article is excellent.

Thank you for sticking with this epic journey!

Further Reading on SmashingMag:

- Unicode For A Multi-Device World

- You, Me And The Emoji: Character Sets, Encoding And Emoji

- Eight Inspiring Stories Of ASCII Art

- The Best Free Fonts for Designers

- Space Yourself

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st

Flexible CMS. Headless & API 1st